Last month, indie game Sektori exploded seemingly out of nowhere onto PC, PS5, and Xbox Series X/S with a gameplay formula that felt instantly familiar. Its pounding techno music, retro-futuristic aesthetic and punchy twin-stick blasting rewound to the early PS3 and Xbox 360 era, when games like Geometry Wars and Super Stardust HD reinvigorated the arcade-shooter formula.

Peeking at Sektori's credits led to the surprise that it was programmed and designed by one person, along with the less-surprising reveal that this person, Kimmo Lahtinen, began his game industry career with 13 years at critically acclaimed Finnish studio Housemarque. We reached Lahtinen via a video call to discuss his decade-plus solo development career, along with how his lengthy Housemarque tenure trickled into one of this year's most addictive games.

Lahtinen grew up in a small town in Finland before moving to Helsinki for university, having fallen in love with computers when his family got a Commodore 64 by the time he had turned 7. He was forced to confront a language barrier at a very young age when he wanted to program his own games: "I of course didn't know English, and every information and manual was in English," Lahtinen says. "You go to a library to search for how to learn this computer thing, but there's only some giant mainframe books."

He doesn't remember exactly how young he was when his interest in making video games began, except to clarify that it began at a very young age - and diverged from fellow Finnish computer fans who fell in love with "demoscene" coding efforts to push contemporary computers to run mind-blowing visual effects. "I wanted to play the demos, not just watch them," he says.

This drove him to, among other things, "save for two years" to purchase his own Pascal compiler, as he had an early interest in coding his own gameplay engines from scratch. He now laughs when recalling what turned out to be a unique path to acquiring expensive software compared to his Finnish mates: "I later realized, 'oh, everybody just pirates this!'" He recalls finishing his first game in 1999 - a Boulder Dash clone named Smilers with a two-player co-op twist - while also playing so many independently developed Finnish games that he ran a game-review website at the time.

While attending the University of Helsinki, Lahtinen applied and was accepted to a three-month game-making course at Housemarque, one of Finland's most successful and longest-running commercial game studios at the time. "I took that and then never left it," Lathinen says. "Career-wise, I've only been at Housemarque as a job - if you don't count summer shops and things like that."

His 13 years at Housemarque did not begin with immediate success, however. The company's last major success before he was hired had been 1999's Supreme Snowboarding, an early DirectX 7 showcase on Windows PCs. By the time Lahtinen arrived, the company had entered a rougher period, with only the 2002 sequel Transworld Snowboarding selling okay. That series' in-development Dreamcast sequel died once Sega pulled the plug, and Lahtinen recalls a flurry of development efforts directed at floundering new platforms, while the company shrunk from 20-30 staffers to "10 at the worst point."

One of these games, a motocross racer for the beleaguered Gizmondo, did launch, while many others didn't. Cancelled and unfinished projects included a Chronicles of Narnia tie-in game for J2ME-compatible phones, an open-world, Elite-inspired third-person adventure called Trader for the PlayStation 2 (see above) and other projects for the Tapwave Zodiac and the Finnish-produced Nokia N-Gage. "We got to see the [N-Gage] prototype beforehand and we were already, like, 'what are they thinking?'" Lahtinen says. "It was a Finnish thing, and I think our guys had connections with the game team that Nokia had. At that point, Nokia kept a lot of Finnish game developers afloat with their projects, but unfortunately it didn't really fly."

From Lahtinen's perspective, jumping from device to device gave him a surprising cushion inside of a tense development environment, as he primarily worked as a gameplay programmer, not an engine one, and thus coded within Housemarque's consistent engine framework. "The engine was quite stable - a platform where we could do things," Lahtinen says. "I was more learning how to do gameplay, make it smartly and just make the games fun. It maybe was quite frustrating that in my first five years, I didn't release a single game that had more than three players. But that period of time really built a foundation that I could actually do games later."

The studio's fortunes turned around with 2006's Super Stardust HD, a revival of the company co-founder's smash 1994 Amiga hit Super Stardust, and Lahtinen continued supporting the studio with gameplay programming efforts for various titles, including work on the technically impressive Super Stardust Portable. He now admits that the biggest lift for getting that PS3 port up to a 60fps update on PSP was to remove all spherical, globe-based rendering for the game's "field" and replace it with "a fake endless plane with the planet rotating on the background." He also points to "writing quite a lot of space partition optimisations to get it all running."

Reduced budget and staff were a common thread for Housemarque projects during his era, which Lahtinen admits bled into his approach to game production in his eventual solo-dev era. "It's a really important thing to get a lot of things on the screen and make it look kind of expensive that way, because we didn't have the $100 million budget to make it expensive just hiring artists and so on," he says. "These demoscene people were always very competitive, too. So if they saw another game doing this, then it's, 'okay, our game is going to do two times that and better.'"

His final title at Housemarque, the stunning PS4 launch title Resogun, actually began life as a PlayStation Vita game, which Lahtinen didn't plan to contribute much to, owing to burnout in the wake of 2011's ambitious, Ikaruga-inspired 3D platformer Outland. Sony reached out to the studio with a simple request after seeing the prototype: "How would you like to do this on PS4?"

Lahtinen jumped at the opportunity, knowing that the prior game's framework could be wholly redone with voxels at its core. "It was a really massive generational leap because we got to play with the compute shaders," he says. "I was quite senior already at that point, and I decided on this project I'm not going to be the responsible adult. I'm gonna be the one to who gets to have all the fun. So I made all these fancy lightings you see in the background, the text flying on the screen and all kinds of compute shader effects we could think of that would take everything out of the pipeline."

He suggests the PS4's sheer power at the time opened up huge programming possibilities with very few performance-based bottlenecks. This opening of technical horizons may have led in part to his next career move.

"I kind of left because I also wanted to do everything else," Lahtinen says. "If you're in a big company and in a big team, I as a programmer can't go to an artist and tell them, 'you need to make this differently because that's how I like it.' You're not the creative lead. And I felt that it was time to strike on my own. And I've really enjoyed having that - now I get to do whatever I want."

This trajectory has included multiple, critically acclaimed smartphone games, from 2014's finger-dragging, top-down racer Drift'n'Drive to 2018's colourful, Diablo-meets-stuffies combat of Barbearian. Lahtinen had plans to never make a sequel and to pivot from one idea to the next for each of his projects - which, in 2015, included an opportunity to quickly produce a game in three months.

"Trigonarium is what I came up with, because I knew I could do a proper shooter - a Housemarque shooter - really simple, really fast, and it had my own engine," Lahtinen says. This fun-but-simple twin-stick shooter stayed in the back of his mind for years, even after finishing an ambitious game that combined match-three puzzle solving with pre-rendered videos, narrative sequences and other content that he describes as "arty."

The 2021 game in question, Day Repeat Day, was his first made in Unity, and the switch from years of making his own mobile-optimised engines was wholly intentional. "There's not much to gain anymore from building your own engine," Lahtinen recalls thinking, "because the computers and phones had started to be so powerful that it didn't really matter anymore if you hardcore optimised it or not." As a less technically demanding game, but also one that benefited from handy Unity benefits like easy support for embedded full-motion videos, Lahtinen saw it as a perfect project to both try new gameplay and learn a new game-making framework.

With Day Repeat Day complete, he looked back at Trigonarium with a couple of new ideas. He completed the original in three months. Building upon that foundation and enjoying some of the development shortcuts of Unity, he could get a sequel done with just a bit more time, he thought. Six months, tops.

"So, if I had at the six-month point known that it would take four more years, I don't think I would have continued," Lahtinen says with an awkward laugh. But time indeed slipped away while making its sequel, which he named Sektori. "At some point I fell in love with this game and just wanted to make the best I could of everything in it."

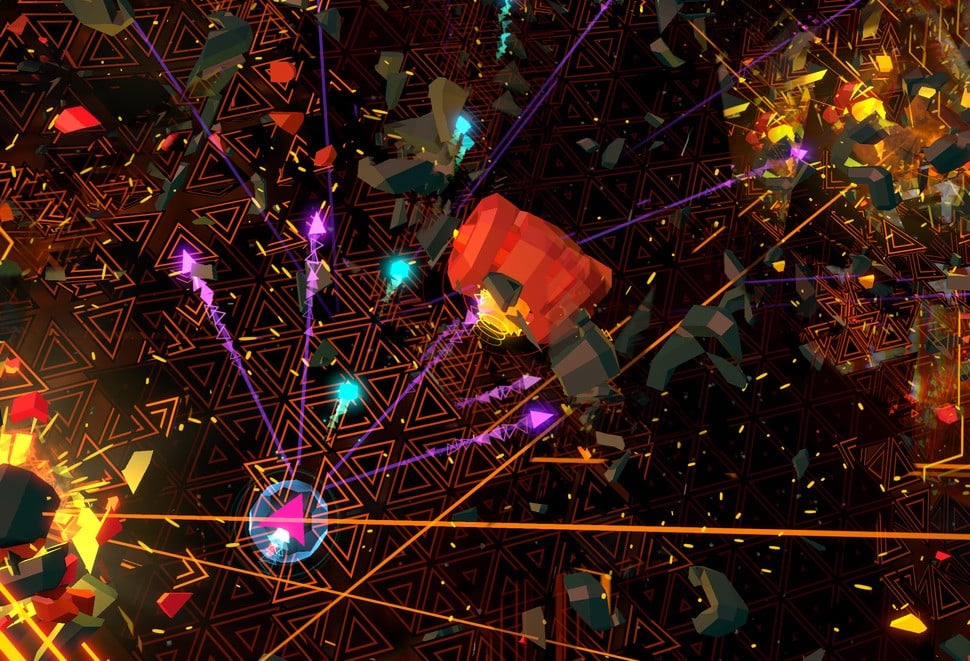

You'll only need a few minutes of hands-on play to agree. Sektori is a white-knuckle-clenching twin-stick shooter borne from the fires that have licked at the likes of Robotron and Geometry Wars. It's a cranked-up evolution of a shooting concept that traps players in tight, arcade-worthy confines, yet regularly mutates and reshapes the battling arena - and offerings roguelite upgrades to help players keep up. This emphasis on an ever-changing environment is joined by a recharging "strike" attack that moves players quickly and slams through the toughest moments, and it's a clever and exciting replacement for the genre's classic, screen-clearing bomb.

Lahtinen suggests that much of the game's development time boiled down to honing its artistic and mechanical core, admitting that he's not a fan of "early access" game launches. "When I released it and submitted it to certification, I thought, I'm 100 percent done," Lahtinen says. "I don't want anyone to see it before it's perfect. That's how I feel at game release: now I can emotionally let it go." For a fascinating glimpse into some of the game's design trajectory, Lahtinen offers a GIF-filled explainer.

He admits reckoning with some of the CPU-demanding elements of Unity in order to reach his goal of a minimum, locked 60fps on a wide range of PC CPUs, in addition to locked 60fps performance on consoles.

"The key thing is always for me that you have a predictable CPU budget for everything," Lahtinen says. "So you don't put in algorithms that have spikes in them. If it drops a frame or three frames at some point, it feels awful. So I always try to build the algorithms so that it might be slower than the best algorithm, but the worst case is still always fine." His custom additions to Unity have included an entity system "so I could control the update order of things" and a collision-management system as the default "introduced weird overhead somewhere else".

"In the past, you had to optimise for the hardware," he adds. "Now, you have to kind of optimise for the engine. So there's one more abstraction level in there. Which is kind of weird but that's the way the world goes."

One issue he could not overcome, sadly, is Unity's CPU cost while trying to run on Nintendo Switch 1. "It ran at 30fps, but I can't release it at that," Lahtinen says. "It has to run at 60fps steadily all the way. That's quite a long leap still to fight, especially when the CPU time isn't going to my code - it's going to Unity code. So you have to find ways to hack around Unity and build your own rendering or whatever is taking time. I believe it could be possible, but it's so much work that it's not very tempting."

As but one CPU-impacting example, Lahtinen says that Unity's "generic 3D pipeline" adds an unnecessary pass of "frustum culling" to in-game objects, which could relieve "a few milliseconds" of CPU impact if removed. That's effort he's not interested in investing in the game at this point - though he makes clear that Unity's many development-pipeline benefits sped development up, instead of slowing it down. He estimates the game could have taken two years longer if he'd tried making the same project with his own engine.

He's also pessimistic about the similar CPU makeup of the Switch 2's Tegra T239 chipset being sufficient to offset issues he's seen with Unity's multi-threaded efficiency on Switch 1. When pressed whether he's confident in his Switch 2 estimation, Lahtinen is emphatic: "I have no clue! It would be super interesting to see. Maybe someone could send me a dev kit and I could try."

At least for existing, compatible platforms, Sektori is an absolute blast with nary a frame-pacing issue or stutter. And Lahtinen offers a fun Easter egg for existing players who might wonder why the game feels more intense as it moves from one level to the next: its music increases a single beat-per-minute in tempo every time. The music, as composed by Lahtinen's brother and longtime collaborator Tommy Baynen, is an imperative piece of its design: "I really wanted this game to sound like you're going into a club and this was like a proper serious techno that you could release in a techno label and be credible," Lahtinen says. "The visuals didn't follow [the music's creation], but they stayed in sync with the music, I think."

Sektori's stylistic similarities to the best of Housemarque aren't lost on Lahtinen, and he admits some of his prior studio's influences have worn off quite clearly. These include a design emphasis on easily readable colours, the impact of the strike attack and the large-text warnings that appear between level transitions. But in his mind, Housemarque's inspiration comes more from the studio's constant push for creativity and maxing out limited resources.

"It was, in a way, a tough environment, because we were a really flat hierarchy, and everybody was doing their best," Lahtinen says. "If you couldn't swim, then you would have trouble there. But I think I thrived in that environment - I could do a lot of things. So when I finally started doing my own things, especially Sektori, I feel like I'm at this point finally starting to understand how to make games."

Comments 6

Downloaded Resogun on my launch day PlayStation 4 — still love it, haven't played it in a while but will now.

However, am absolutely loving Sektori on Steam Deck, the inky blacks versus the beautiful and fast graphics, the visual design is top notch as is the gameplay. Cannot recommend this enough.

So good that it may have to get a double-dip with PlayStation on the OLED television. Gorgeous.

I very much enjoyed Geometry Wars back in the day so after DF recommended this I grabbed it straight away. It was refunded very quickly.

Not because of the game, which is basically a perfectly competent geometry wars derivative, but because of the music. As John has said many times in his videos, music is a critical part of any media, and Sekitori's choice of head banging atonal techno was about as appealing as a trip to the dentist. A good shooter (see pretty much anything by Technosoft) needs some catchy tunes. Sekitori failed completely in this front so for me at least it was a deal breaker. I realise music of all things is subjective, so for some I imagine this will be a non issue, or maybe I'm just too old school. But I'd take the soundtrack to Thunderforce 4, Hyper Duel, Ikaruga, or Axelay over whatever it was in Sekitori in a heartbeat.

As a fan of Sektori's OST, and a believer in its mission statement of "real techno" as a thumping, driving undercurrent to propel its action along, I'll use this opportunity to share its portal for those who want to sample, stream or even buy the music outright: https://tommybaynen.hearnow.com ... and it's also available as a Steam purchase. I didn't get into it in the article, but Lahtinen also custom-made the FMV light-show sequences that play behind the action, and they're made in part to pair with the music.

Excellent game and excellent feature. Just found out imgur is banned in the UK though so can only imagine those joyful GIF-filled explanations 😆

Bought it directly. Great fun that DF push indie games too!

@ramu-chan For a straight arcade game, you likely would have made up your mind by watching the trailer. The rate of refunds may affect a game's visibility on Steam and Valve also pays the payment processor fees (which are likely baked into their default 30% cut).

Show Comments

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...