Raspberry Pi: a complete, credit card-sized computer for just over £20. The concept is intoxicating, the possibilities endless. Potentially, what we are looking at here is a revolution in entry-level computing and programming, a completely open platform gifted by a not-for-profit charity to the next generation of coders, engineers, enthusiasts and innovators. Born in Britain, Raspberry Pi could genuinely be the next "big thing" for home computing and so much more.

So what's the big deal? What separates the "Raspi" - as it's colloquially known - from the multitudes of computing options we have at the moment? For a start, the amount of processing power at such a low cost is truly astonishing, and the unique set-up behind the project helps make this miniscule price-point possible. The Raspberry Pi foundation isn't out to make money - its trustees offer their time and expertise for free and any profits made are ploughed back into the charity. There are no sales targets to achieve or shareholders to appease; the team has its vision and that's the only focus.

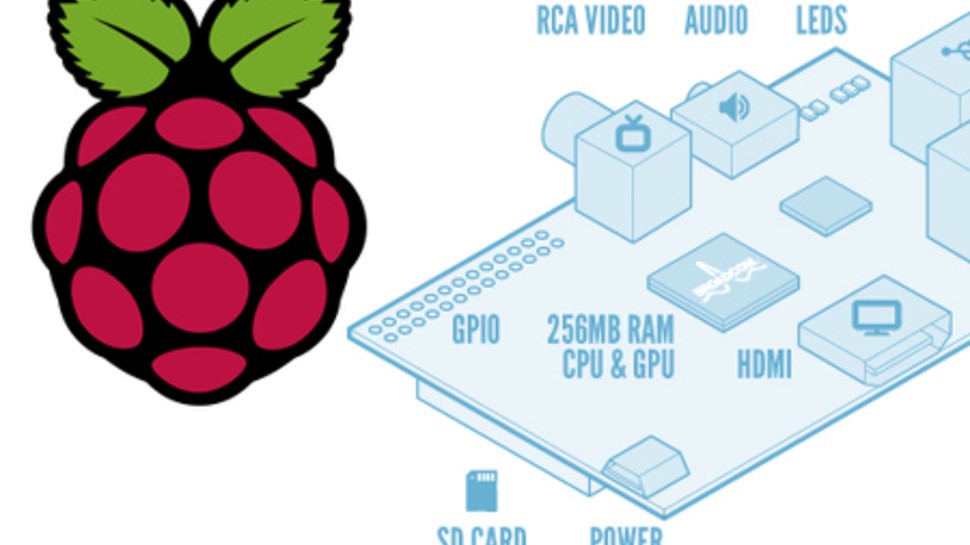

Keeping costs to a minimum is the fact that there are no licensing costs to pay on the operating system either. Raspberry Pi will run whatever OS is available and compatible. The older ARM architecture it hosts won't run the forthcoming Windows 8, but a couple of versions of the free, open source Linux OS are already supported, while Google's Chromium OS is also in the process of being ported to the fledgling computer. Buy your Raspberry Pi and all you need to get going is a keyboard, mouse, display (monitor or TV) - and an SD memory card on which to host the OS.

The Form Factor

Raspberry Pi: The Programmer's Perspective

Digital Foundry spoke to programmer Liam McLoughlin (hacker alias: Hexxeh) to get a coder's view on the new device. Hexxeh compiled Raspi binaries for Quake 3 Arena, is working on a port of OpenTTD (Transport Tycoon) and is also intent on bringing the Chromium OS to the fledgling computer.

Digital Foundry: What initially interested you about the Raspberry Pi?

Liam McLoughlin: I became interested in the device last summer after seeing an early version on BBC News and the idea of a super cheap and small Linux computer very much appealed to me. Having worked on Chromium OS for a while, I knew there was ARM support in the codebase but I'd not worked with it very much.

I'd seen development boards like the Pandaboard and Beagleboard before, but they're considerably more expensive, more than I wanted to pay for a toy really. That said, something like the Pandaboard has significantly more computing power and so it's probably better suited to Chromium OS. There's a bit of a challenge involved in working with cheap hardware like the Raspberry Pi, though. It's more fun if it's not entirely straightforward, whereas I expect running it on the Pandaboard would be.

Digital Foundry: What were your first impressions of the unit?

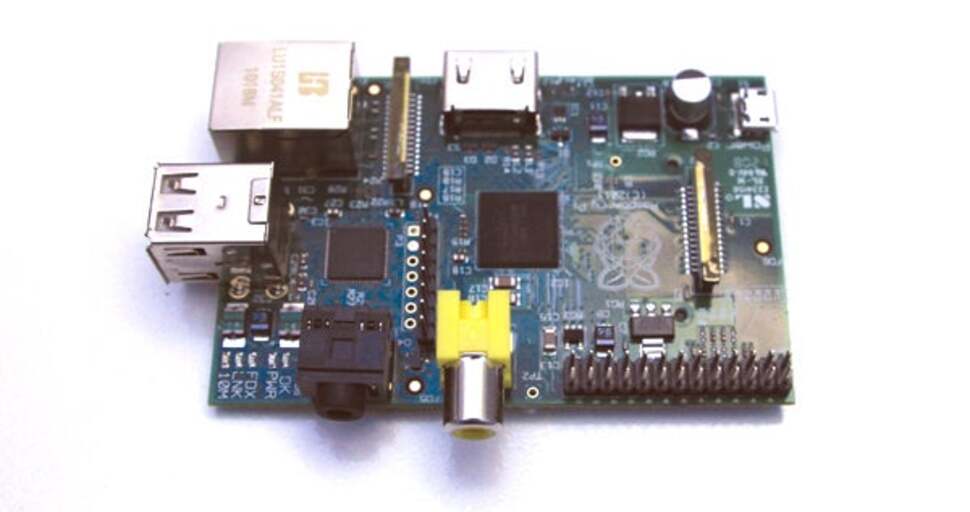

Liam McLoughlin: The first thing that struck me was the size of the board, it's tiny! It's the same kind of chip you'd normally find in a mobile phone, but you don't get the same kind of excitement seeing it in a phone. There's just something really cool about seeing a tiny board working as a traditional desktop computer. I had a quick play around with Debian, and then set to work bringing up Chromium OS on the board. I think I pretty much lost the rest of that day to the Pi...

Digital Foundry: What's your take on the CPU and GPU components in the Pi?

Liam McLoughlin: I think many people overestimate the power of these components, particularly the CPU. With demos like XBMC and Quake 3, many people probably assume the device is faster than it really is. The GPU is pretty powerful but it's very much suited to perform-specific tasks like video decoding. If you're expecting to play Minecraft on this thing then forget it, not on 256MB of RAM. I think the CPU was compared to a Pentium 2 or something like that? It's really no speed demon, but it is excellent value for the price you pay.

Digital Foundry: Python seems to be the preferred language Raspberry Pi is championing for homebrew development. What's your assessment of it and how well suited is it to the device?

Liam McLoughlin: Python is a very simple language to pick up, it's intended to be simple for beginners to programming to pick up, but at the same time it's also very flexible and powerful. It strikes a good balance between usability and flexibility, so I'd say it's an excellent choice.

Digital Foundry: You've released Quake 3 binaries and you're working on bringing OpenTTD (Transport Tycoon) to the Pi. Tell us about that.

Liam McLoughlin: Quake 3 was a simple compile, the code was already provided pre-modified on the Raspberry Pi Foundation's GitHub account, but no binaries were provided. Since cross-compiling isn't everybody's cup of tea, and compiling the game on your Pi takes a rather long time, I thought I'd make it easier for people who'd just got their Pi to quickly try out a demo and see what it can do.

I'm working on OpenTTD at the moment, since this was one of the first games I ever played as a kid (not the open-source version, the original Microprose version). It runs pretty well as you'd expect for a fairly simple 2D game but I'm making a few tweaks to have it run even better on the Pi before uploading binaries. The Pi requires a couple changes to get some titles to run at all, there's a call you need to make to set the connection between your program and the VideoCore chip up to get 3D graphics running.

Digital Foundry: You're in the process of porting Chromium OS to the Raspi. To what extent is the lack of hardware acceleration an issue?

Liam McLoughlin: It's basically a showstopper issue. I've got things running without the acceleration and it's basically painful to use. Hopefully we'll see the beginnings of a Xorg driver in the coming weeks/months as more developers get their hands on devices.

Digital Foundry: Bearing in mind the memory split situation with the 256MB RAM, to what extent is it a good thing that the Model A Raspberry Pi has been bumped up from its initial 128MB?

Liam McLoughlin: I'd imagine having to split just 128MB of RAM would've proved rather painful. The upgrade to 256MB was fantastic news, since it meant that software that works on the Model B should also work on the Model A, since they're identical except for their USB/Ethernet ports.

Digital Foundry: There's a sense that the hardware is complete but the software is some months away from being viable for the layman. What are your thoughts on the launch thus far?

Liam McLoughlin: I agree completely. The software, in my opinion, really just isn't ready for your average user, who takes things like a hardware accelerated desktop environment for granted. I think that developers should've really had a couple of months' head-start to get the software into shape before users started to get their hands on them. I expect that we'll see more and more of the devices ending up on eBay as users discover that the Pi can't do everything they thought it could, partly due to missing software. Of course, some people just have silly expectations of what the Pi can do altogether, which can never be met with improved software.

Digital Foundry: Is the potential there for the Pi to evolve into a solid "everyman" PC capable of browsing, office work, video playback etc?

Liam McLoughlin: No doubt people will make it do all of the tasks you mention, I think it's a case of how well it can perform those tasks. I think in time, we'll see all the tasks you list working well, but we're definitely not there yet.

While the PCB itself is roughly credit card sized, the Pi itself is a little stockier when viewed in three dimensions owing to the range of ports attached, coming in at 85.60mm x 53.98mm x 17mm, with a little overhang from the attached SD card. AV outputs consist of a standard HDMI port, backed up by RCA composite video and a 3.5mm stereo jack for analogue support. A GPIO interface on the board allows the Pi to interface with the outside world, giving it plenty of potential for finding its way into a multitude of homebrew engineering projects. Adding some height are two USB ports stacked one on top of each other (use a hub to attach more devices) while power comes from a micro-USB socket - the same kind of connection used in many mobile phones.

An existing cellphone charger should do the trick in powering the device, but it can also run from a powered USB port too - it operates with no problems from both a PS3 and a desktop PC, though the Raspberry Pi Foundation doesn't recommend laptop USB ports for the task owing to variances in the power output on some machines. With the main processor under load, the Raspi gets warm to the touch, but despite featuring no active cooling it never gets hot.

Although currently supplied in barebones form, certain future versions of the Pi will come mounted inside a case (an on/off/reset switch would be useful too) and once there's decent volume out there we should expect to see a range of third-party enclosures too.

In terms of the architecture, much has been made of Raspberry Pi's processor - the Broadcom BCM2835 - a SoC (system on chip) that is designed primarily for the mobile market. A 700MHz ARM1176JZFS beats at the heart of the design, with graphics support provided by Broadcom's VideoCore IV technology. This exact silicon powers the Roku 2 media player, and while Angry Birds has been shown running on this smart little box, Raspberry Pi is the first device to give its 3D capabilities a decent work-out.

Getting Started with Raspberry Pi

Initial set-up is relatively straightforward - with a couple of caveats. Just like a normal PC, you need to set-up an operating system before you can get anything meaningful from the device. This is achieved by acquiring an SD card, grabbing an OS image from the Raspberry Pi website, and then writing it to the card. Pre-prepared cards will be available over the course of time, but in the here and now, you'll need an existing computer to do this. Plug the primed card into the Pi, attach the USB power and you're on your way. Hopefully.

In the here and now, Raspberry Pi is somewhat fussy about the SD cards you can run with it. We hoped to compare the Class 4 Transcend card supplied with our review unit with a 16GB Class 10 Sandisk "Ultra" card, capable of 45MB/s read speeds (a snip at just £16 from Amazon). We were curious to see if the high-end cards could provide a faster-booting, more responsive desktop. Unfortunately, the Pi didn't work with it at all - though a forthcoming firmware update should hopefully resolve this.

Currently, the Debian "Squeeze" Linux distribution is the flavour of the open source Linux OS that's recommended to get the show on the road. Booting it up reveals an OS that looks rather like a cut-down version of Windows XP: minimalist, functional, and not quite as intuitive as the operating systems you may be used to. However, it is fast to load - even from a Class 4 SD card - and all the tools you need are easily accessible.

Once you get going, first impressions may not live up to expectations - and it's important to understand why. The big issue with Raspberry Pi in the here and now is that there is no hardware acceleration of the desktop and as such the OS feels clunky and very unresponsive, with navigation and movement of windows often feeling lumpen and slow. Functionality elsewhere is also limited. The Midori browser included doesn't support HTML5 or Java, and there is no support for Flash (and the Adobe platform is unlikely to be implemented). Web browsing is therefore an exercise in patience and you'll need to be prepared for the fact that there's a lot of online content you won't be able to access.

The vision of the Raspberry Pi as an everyman computer capable of web-browsing, office work and media playback really isn't there yet - but it's important to stress that the software is in the very early stages of development. Hardware acceleration and support for HTML5 is a must for transforming Raspberry Pi into a more user-friendly, content-rich experience. OpenGL video acceleration of the OS is currently a priority for the Raspberry Pi foundation - and is being worked on now in conjunction with a "couple of partners".

Gameplay Credentials

The BCM2835 chipset inside Raspberry Pi has some impressive 3D power on tap. Although the Foundation now plays it down, from a GPU perspective it should be able to compete well with just about any mobile graphics solution on the market. However, it should be noted that the CPU is under par compared with competitors, so in advanced gameplay applications, there is the danger that there's simply not enough processor horsepower to keep the GPU fully occupied.

While Open GL ES 2.0 and OpenVG support are incorporated into the Pi, once again there's a strong feeling that we're at really early stages of development here. Obviously, games are few and far between at the moment, but a version of id software's classic Quake 3 Arena has been made available, ported to Raspberry Pi by the foundation itself, while more Linux ports are in the offing - the open source rendition of the classic Transport Tycoon should be available very, very soon.

However, it's Quake 3 that's the focus in the here and now. Performance analysis suggests that the Pi can run this port of Q3A at between 20 to 60 frames per second, seemingly regardless of the graphical settings that are enabled (quality settings appear to be locked on the version we were supplied with, so the settings menu in the demo is mostly for show only).

Quake 3 Arena is a 1999 title running on the classic idTech 2 engine. In truth, the overall level of performance and graphical fidelity we see here is lower than we might have expected bearing in mind what the VideoCore IV should be capable of, but as a basic port running on early software, hosted on a £20 computer, you can argue that it's a miracle that it's as good as it is.

Going forward, developers of more ambitious games may feel slightly hamstrung by the memory set-up of the Pi. The unit has 256MB of RAM in all - but this needs to be shared between the CPU and graphics core. This doesn't happen dynamically, the user needs to set a specific split. Three options are available right now:

- 224MB CPU/32MB GPU

- 192MB CPU/64MB GPU

- 128MB CPU/128MB GPU

Quake 3 Arena won't even load if you're using the 224MB/32MB arrangement, and the OS set-up given to us by the Raspberry Pi Foundation was set up to allow switching between the two extremes. On our supplied SD card, attempting to load an application that requires more video RAM brings up an error message, but does offer to reset the RAM allocation and reboot the device. It's not 100 per cent ideal, but at least the hard work is done for you and there are no ugly crashes to contend with.

XBMC Media Playback: Easy as Pi?

Media consumption is a big deal for a lot of people, and the Raspberry Pi has been viewed as a cheap way to potentially add advanced media playback facilities to any HDTV. In theory, as the Broadcom chipset at its heart is already being used in a commercial media player, the Raspi should be a sterling performer. The BCM2835 handles h.264 decoding up to 1080p at 30 frames per second, with bandwidth up to 40mbps - that's Blu-ray level performance.

But as our experience with the Raspberry Pi thus far demonstrates, having the requisite hardware at your disposal means little if there's no software to run it. Thankfully, the XBMC media portal has been ported to the Raspberry Pi - and it features full hardware acceleration for video decoding. The interface is a little slow (especially so if set to 1080p) and movie files can take a while (sometimes a long while - 20 seconds or more) to begin, but there's no denying the quality of the playback.

We managed to run 1080p24 and 720p60 h.264 content in both MKV and MP4 containers with no problems whatsoever, while standard definition XviDs also ran without a hitch. We weren't able to test HDMI audio bitstreaming (though the option appears to be present) but sound playback didn't seem to cause any issues - even DTS HD was decoded. Setting the Pi to native Full HD video output and trying to run a 1080p MKV with DTS HD audio was the toughest work-out we could come up with and while the frame-rate dived when the OSD was brought up, the overall playback experience was fine. We even went beyond the spec by giving it a 20mbps 1080p60 video to chew over and while some frames were dropped and audio gradually slipped out of sync, the Pi still gave its best. Impressive stuff.

The version of XBMC on our press image also supported USB drives formatted into both FAT32 and NTFS formats - the latter is a Windows system that allows for files over 4GB in size (virtually any feature length high definition movie file) and compatibility is often neglected. Not here though; in virtually all respects, the Raspberry Pi acquitted itself very well and the video above is a good representation of general performance.

Suffice to say, the XBMC experience was one of the highpoints in checking out the Raspberry Pi in its present state. We had some issues with USB drive stability (the 1080p/DTS HD stress test didn't work one day, but was fine the next day) but overall impressions were highly favourable. Once the initial difficulties and bugs have been ironed out, Raspberry Pi should be a superb little media player that really plays to the strengths of the underlying hardware.

Raspberry Pi: The Digital Foundry Verdict

What we have at the moment is a hint of what the device is capable of. There are tantalising glimpses of some wonderful things to come but from a software perspective, it remains a work-in-progress.

A virtually complete computer for just over £20 - Raspberry Pi is a truly remarkable initiative with a wealth of potential. The bottom line is that the hardware is there, but it's difficult to avoid the conclusion that the device is some way off being a viable entry-level consumer computer in its current form, its charms best appreciated by developers and tinkerers. In its present state, the average user might be disappointed by the general performance - and it may well be that the continued delays in getting mass volume out to the hundreds of thousands of Raspi owners-in-waiting could well turn out to be a blessing in disguise. Hopefully, improved software will be available by the time the device starts to ship in serious numbers.

In terms of what the Pi offers right now, rudimentary browsing is possible - if you have the patience for it - but the lack of hardware acceleration in the core OS is a killer, severely impacting the "handshake" between the user and the OS, making general usage feel unsatisfactory. While the Pi can still be used even in its current form for learning how to program, it really needs to establish itself as user-friendly, useful computing platform for the everyman - then it stands its best chance of converting users into programmers, just like the BBC Micro and ZX Spectrum did back in the day.

In a sense then, even with a unit in our possession primed with an OS and demos supplied by the creators of the hardware, it's almost impossible to pass any kind of definitive verdict on the Raspberry Pi in the here and now - it's just too early. What we have at the moment is a hint of what the device is capable of - an alpha release if you like. There are tantalising glimpses of some wonderful things to come but from a software perspective, it remains a work-in-progress.

In terms of the hardware itself, the scale of the Foundation's achievement cannot be understated. At the very least it has created a brand-new platform that is set to enthuse homebrew experimentation for years to come - and hopefully it will evolve into the coding kickstarter it was originally envisaged as. Ultimately, Raspberry Pi may very well be the trailblazing product that defines a new "ultra-barebone" market sector for portable computing. Indeed, with the likes of the 1.2GHz Cortex A8/Mali 400MP A10 "Allwinner" SoC finding its way into sub-£100 Android tablets, this could happen sooner rather than later.

Exciting times ahead then, and we'll be following the evolution of Raspberry Pi with much interest - and it's hugely satisfying to see British innovation and engineering at the forefront of what is an astonishing piece of kit.

Comments 0

Wow, no comments yet... why not be the first?

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...